We’re in the midst of a frenzy of urban sketching book releases and I’m downright giddy about it. For a long time our single reference was Gabi Campanario’s The Art of Urban Sketching, that introduced the topic and presented examples from around the world. Then the architects stepped up and we heard from James Richards and Matthew Brehm who breathed some rigor into discussions of approaches to sketching/drawing and their books were a boon to the community. Thomas Thorspecken gave us a book that was mostly about sketching scenes full of people, with answers to the where-to-do-it and how-to-do-it. Gabi has a new book that builds on his first, providing more detailed insights into the various kinds of urban sketching being done.

The popularity of urban sketching is soaring as the art world rediscovers that drawing is still the foundation of art and we’re being shown the way to enjoy art in our own backyards and city streets. This is all to the good. The downside, if social media is any indication, is that a lot of people with considerable art skills struggle because location sketching is not like studio art, either in its expectations or its approaches. And while every urban sketching book to date acknowledges those differences, provided solutions can be boiled down to “draw faster and don’t expect a masterpiece.”

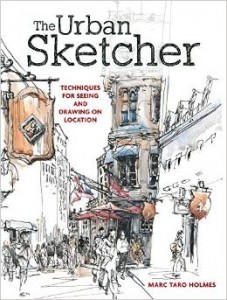

Marc Taro Holmes has just released a book, The Urban Sketcher: Techniques for Seeing and Drawing on Location, that directs its attention to these issues specifically. Before discussing his book I need to say what this book is not. It is not a introduction to drawing book. Marc starts with the assumption that you know the basics of drawing and/or you have a book that will teach them to you. There are no long sections explain what paper, pencils and pens are, though he does mention his favorites so you know what’s being used to create the workshop he presents. There are no drawn out discussions of perspective or where the eyes go on a human. There are no discussions of color theory. He assumes you know this stuff.

Marc Taro Holmes has just released a book, The Urban Sketcher: Techniques for Seeing and Drawing on Location, that directs its attention to these issues specifically. Before discussing his book I need to say what this book is not. It is not a introduction to drawing book. Marc starts with the assumption that you know the basics of drawing and/or you have a book that will teach them to you. There are no long sections explain what paper, pencils and pens are, though he does mention his favorites so you know what’s being used to create the workshop he presents. There are no drawn out discussions of perspective or where the eyes go on a human. There are no discussions of color theory. He assumes you know this stuff.

He assumes you can draw the buildings, cars, plants and people in his examples slowly, while sitting in your studio. His concern is for how to do it when your time is limited, when your subjects are moving, and when you’re out in the elements. The entire book centers on how to sub-divide drawing to minimize the number of things you have to think about and capture at any one time, with the goal to speed up and compartmentalize each step. And oh boy…does he do a fantastic job of that.

The book is done in workshop style, with explanations, demonstrations and then with exercises. He warms up to the subject by telling us how cool urban sketching is, why we should do it, and how a simple sketchbook and pencil are all that’s needed to get started. But the bulk of the book consists of three chapters:

Chapter 1 – Graphite Draw Everything You See

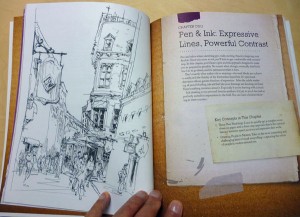

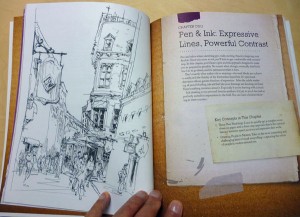

Chapter 2 – Pen & Ink: Expressive Lines, Powerful Contrast

Chapter 3 – Watercolor: Bring Sketches to Life with Color

Chapter 1 – Graphite Draw Everything You See

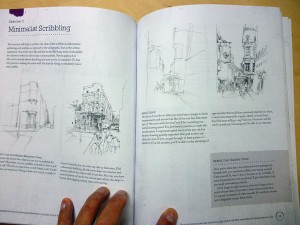

This is the shortest chapter, but it’s the basis for the other two. Marc is an advocate of the divisive, rather than additive drawing. He calls it “outside in.” No matter what you call it, it simplifies the drawing process and won’t leave you saying “oh, I ran out of room for his feet.” Mostly outside-in allows you to organize in such a way that you can draw parts of a scene or object with the full knowlege that one part will fit with the next.

This is the shortest chapter, but it’s the basis for the other two. Marc is an advocate of the divisive, rather than additive drawing. He calls it “outside in.” No matter what you call it, it simplifies the drawing process and won’t leave you saying “oh, I ran out of room for his feet.” Mostly outside-in allows you to organize in such a way that you can draw parts of a scene or object with the full knowlege that one part will fit with the next.

He starts this discussion with some standard measuring methods and provides insights into their use. This is similar to Matthew Brehm’s discussion of this crucial, and oft-overlooked step. Marc has a section on the use of shading to provide depth to your drawings as well. His discussion of “gradient of interest” is worth reading and practicing he uses several methods to draw the viewer’s eye to whatever it is you choose to be the main subject of your sketch. This also provides some solutions to the problem of the endless urban landscape and how to deal with the edges of any particular sketch.

The outside-in approach alone can cut your drawing time in half but all of the things in this chapter can help an artist whether you’re working in a studio or on the street.

Chapter 2 – Pen & Ink: Expressive Lines, Powerful Contrast

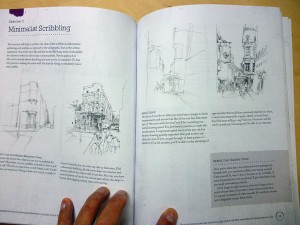

Here’s where Marc picks up the pace and attempts to increase yours. He presents his three-pass sketching approach. Drawing is a complex skill. An artist must deal with the dimension and shape of each object as well as their relative locations. He/she must think about the actual shape of each of those objects and then there’s the matter of shading and, possibly color. It’s too much when you are trying to draw something transient and everything in an urban landscape is transient. Even buildings reflect constantly changing light regimes. So, what to do?

Here’s where Marc picks up the pace and attempts to increase yours. He presents his three-pass sketching approach. Drawing is a complex skill. An artist must deal with the dimension and shape of each object as well as their relative locations. He/she must think about the actual shape of each of those objects and then there’s the matter of shading and, possibly color. It’s too much when you are trying to draw something transient and everything in an urban landscape is transient. Even buildings reflect constantly changing light regimes. So, what to do?

Marc’s answer is scribble (capture the proportion and relative relationships), calligraphic line drawing (do the actual line drawing), and spot blacks (add shading/contrast to improve depth/form). He walks you through several demonstrations of this technique and it’s invaluable, though I’m still struggling with the scribble portion myself but it’s brilliant as even if your subject leaves, you’ve still got the overall shape upon which to generate an actual drawing.

Once the basic technique is described, Marc moves on to people, specifically people in motion. Here’s where many give up. “They move too much,” it’s often said. From my own experience I’d say they’re right about that moving stuff but Marc shows how to apply his 3-pass approach to this dilemma and adds to your sketcher toolkit the notions of compositing people (using several models to produce one sketch) and multitasking (working simultaneously on multiple views of a character in motion). His sections on drawing people represent a significant number of pages of this book and I’m still in the process of consuming them. I hope to spend the winter months practicing these techniques.

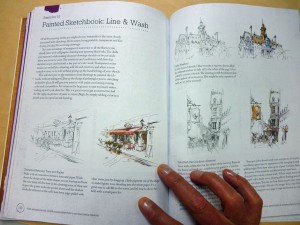

Chapter 3 – Watercolor: Bring Sketches to Life with Color

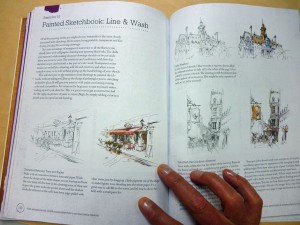

Marc opens this chapter with a quick description of his materials and a few of his favorite watercolor techniques, like charging-in, and edge-pulling. Good stuff all but the real power of this chapter comes from sections on using sparing amounts of watercolor to bring pen & ink drawings to life and to further direct the view to the center of attention. He also provides an interesting view that most scenes have “three big shapes”, the sky, ground, and subject. He admits that it’s never that simple but that approaching watercolor with that in mind allows one to better structure your color.

Marc opens this chapter with a quick description of his materials and a few of his favorite watercolor techniques, like charging-in, and edge-pulling. Good stuff all but the real power of this chapter comes from sections on using sparing amounts of watercolor to bring pen & ink drawings to life and to further direct the view to the center of attention. He also provides an interesting view that most scenes have “three big shapes”, the sky, ground, and subject. He admits that it’s never that simple but that approaching watercolor with that in mind allows one to better structure your color.

The centerpiece of this chapter, though is his Tea, Milk, Honey approach to watercolors that he has advocated over the past couple years. If you’re familiar with his work you’ve probably seen it via the internet. It’s essentially a 3-pass approach to watercolors, using every thicker washes and increasing detail to complete a painting. I think it’s not much of a stretch to equate Tea = scribble, Milk = drawing line and Honey = spot blacks to bring things back full-circle to his 3-pass sketching approach, though the Tea, Milk, Honey approach does rely upon on pen or pencil sketch as its foundation.

We live in an era of rebirth for drawing and Marc’s book, in my opinion, will become one of the cornerstone books of that rebirth. I know that sounds like hyperbole but I own a lot of drawing books and most of them don’t seem to understand the notion of structuring a drawing before you draw details, dividing the process of drawing into sub-goals that capture particular aspects of the scene being drawn. And yet, when I watch professional artists draw, they ALL do this, whether they realize it or not. Buy a copy of The Urban Sketcher: Techniques for Seeing and Drawing on Location. Become better at what you do.