As a guy who has only been drawing for a couple years, I’ve noticed some things about the art world. First, and foremost is that many so-called “fine arts” schools have largely abandoned notions of realism in art and many have abandoned drawing as a base skill. Those who draw are directed to graphic design and/or animation departments. While this surprised me, I was a hobbyist and what happened in art school didn’t, I thought, affect me much.

And so I did what most hobbyist artists do. I bought lots of books on drawing and watercolors and I’ve tried to learn some of what was contained within them. If one buys enough of these you know that many present a series of “lessons” where the first sentence is something like “We first start with a sketch.” The lesson goes on to teach whatever aspect the lesson is meant to cover. How one gets the ‘sketch’ is left to the reader to figure out. I relied upon hobbyist ‘drawing’ books to learn what I could about that process.

Then I met my buddy and mentor, Yvan Breton. He is an architect and an accomplished artist. He started teaching me concepts like scaffolding, multiple plane thinking, use of the terminator, line thickness variation and other concepts that I had not seen discussed in the drawing books I’d read. He showed me how Rembrandt used these concepts in his art.

Initially I was reluctant to ‘add’ to what I was doing as a street sketcher, believing these ‘extra’ things would only add time to the process. Oh, how wrong I was. I’m still working to incorporate these ideas into my own sketches but as I do, my sketches have become better and my drawings are done more quickly and with better unity. I still need much practice but I’m beginning to see why it is that good artists are, well, good artists. More perplexing to me was why, if all the masters, like Monet, Renoir, Rembrandt, Raphael, etc. knew about these things, did I see so little evidence of the concepts in my drawing books.

This led me back to the abandonment of traditional methodologies by fine art programs, which led me, in turn, to the “atelier movement” which seems to be taking place around the world. Small(ish) art schools, independent of universities, that are teaching what are called “foundational” art skills. I have no first-hand information of these schools except that they sound like the old apprenticeship programs that existed in the woodworking world.

This led me back to the abandonment of traditional methodologies by fine art programs, which led me, in turn, to the “atelier movement” which seems to be taking place around the world. Small(ish) art schools, independent of universities, that are teaching what are called “foundational” art skills. I have no first-hand information of these schools except that they sound like the old apprenticeship programs that existed in the woodworking world.

These ateliers make no bones about the fact that they are teaching what they teach because only by knowledge of these principles and methods can an artist have the tools to produce art. They quite explicitly argue that the singular emphasis on ‘imagination’ by art schools is akin to teaching students to have the imagination of Jules Verne but not the technical expertise of a rocket scientist and then expecting the student to go to the moon. Only by mastering foundational art skills, they say, will an artist have the freedom to succeed as an artist.

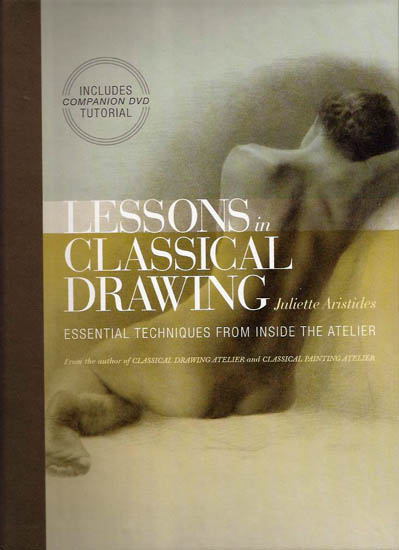

From these discussions I found myself looking for books that cover those foundational skills and I got lucky to find Juliette Aristides, who started a ‘classical’ atelier. More important, she has written three outstanding books on the subject, the first of which is Classical Drawing Atelier, followed by Lessons in Classical Drawing. Her third book is something of a parallel that deals with painting. These two basic books, however, contain more information in them about drawing than ALL of the hobbyist drawing books I own. Rather than the typical piecemeal “here is perspective”, “here is foreshortening”, “here is tone”, she presents drawing as an integrative process. The second book, is more than just a series of lessons about what is in the first book. Rather it is an extension of the first book and the two work in concert to teach you to draw the way the greats did it. And you know what? It’s a LOT easier to deal with things like perspective, foreshortening, and composition if you view them as a whole than by viewing them as separate issues. This is why the drawings of good artists seems so much more unified than those of most of us.

From these discussions I found myself looking for books that cover those foundational skills and I got lucky to find Juliette Aristides, who started a ‘classical’ atelier. More important, she has written three outstanding books on the subject, the first of which is Classical Drawing Atelier, followed by Lessons in Classical Drawing. Her third book is something of a parallel that deals with painting. These two basic books, however, contain more information in them about drawing than ALL of the hobbyist drawing books I own. Rather than the typical piecemeal “here is perspective”, “here is foreshortening”, “here is tone”, she presents drawing as an integrative process. The second book, is more than just a series of lessons about what is in the first book. Rather it is an extension of the first book and the two work in concert to teach you to draw the way the greats did it. And you know what? It’s a LOT easier to deal with things like perspective, foreshortening, and composition if you view them as a whole than by viewing them as separate issues. This is why the drawings of good artists seems so much more unified than those of most of us.

In addition to the books, the second book comes with a instruction DVD where Aristides walks you through the development of four separate drawings. I’ve only watched it twice thus far but I’ve found it, like the books, to be invaluable. I should mention that while the book covers suggest these books are about life drawing, they are not exclusive to it. In the DVD, for instance, Aristides uses an old pair of boots as one of its subjects, a large pitcher as another. The techniques can be applied to and will improve any drawing. If you’ve been drawing for a while and woud like to improve, give these books a try as unless you’re already an accomplished artist, some practice of these methodogies will not only improve your drawings, it will make them easier to do.